2021 Stagecoach 400 Race Recap - The Great Burrito Truce

By Matteo Pistono

This 2021 Stagecoach 400 marks the 10th edition of the longest bikepacking race in California. After more than a year of pandemic, lockdowns, and race cancellations, excitement had built among the riding community in San Diego and beyond. For many of the participants, this was the last race they attended back in 2020, as the country shut down following last year’s start. Online registration for the 2021 event filled within hours. Riders looked to traverse the region’s diverse set of biomes across nearly 400 miles of challenging terrain. April 9th, 2021 was the Grand Depart.

Remote single track and fire roads comprise most of the Stagecoach 400 route. PC: Matteo Pistono

The Stagecoach 400 descends from the pine forests around Idyllwild at 5,400 feet above sea level to the arid, rolling desert hills around Anza and Ramona, and then it turns south along the Pacific Coast to arrive in San Diego at mile 160. The route then climbs east on flowy single track, rock gardens and truck trails over the Cuyamaca Mountains through Alpine and then descends gnarly, enduro-style valleys to the edge of the Anza-Borrego Desert at mile 264. “Here the sand begins. Dig Deep. You’ll be questioning your life’s decisions,” the route designer, Brendan Collier writes in the cue sheet. Across the sand towards Ocotillo Wells and pot-holed tarmac into Borrego Springs, riders often meet 30-40 mph headwinds before they enter Coyote Canyon, a long stretch of the route that includes pushing their bikes in deep sand, hiking through a mile of the Middle Willows swamp, and climbing over chunky ATV-wrecked trails. The old cattle rustler hide-out of Bailey’s Cabin offers respite before the 4,000-foot climb up the mountain towards the granite peaks surrounding Idyllwild at the finish.

The Challenging 30 mile stretch of washboard across the Anza-Borrego Desert. PC: Tim Tait

The race route passes through a number of Native Indian lands; those of the Luiseno, Cahuilla, Cupeno, Kumeyaay, and Northern Diegueño tribes. The race takes its name from the historic Stagecoach routes it crisscrosses, including the Juan Bautstita DeAnza trail, the Great Southern Overland Stage Route of 1849, and the Ramona Stage Route.

The Stagecoach is a non-sanctioned, unsupported event. “Unsupported” or “self-supported” means that riders need to be completely self-sufficient. Riders may use any facilities (food shops, restaurants, lodging, etc.) that are available to other racers, but they are not allowed to receive planned, outside support. Food for Stagecoachers is principally comprised of gas station candy bars, soda and chips. Burritos are a primary nutrition source and are often seen strapped near handlebars for snacking while pedaling.

Precipitation and heat play a critical factor every year in the Stagecoach. In 2020 there were biblical levels of precipitation before and during the race, so much so, the course was drastically rerouted around the flooded roads and impassable peanut-butter lakes of mud. Less than thirty riders began the race last year in the snow, and only half of them finished.

This year the roads were smooth and bone dry, and spiking temperatures in the 90s impacted the race. A strong group of 20 riders set a blistering pace from Idyllwild across the Land of a Thousand False Summits beyond Anza and towards Black Canyon and Pamo Truck Trail. A dozen riders succumbed to heat exhaustion in the first 100 miles, some vomiting along the course, others taking shelter under oak trees trying to lower their body temperature, some calling their spouses for a roadside pick-up.

The three lead riders, Tim Tait, Gregg Dunham and Marilyn Rayner pedaled throughout the night. None of them carried a sleeping bag or pad, only an emergency foil blanket. They rode separately south along the Pacific Coast through San Diego, ascended the mountain trails past Alpine and the Cuyamaca Mountains (mountain lion tracks were spotted on top of their bike tread tracks by riders behind them) before the chunky single track and truck trail descents towards Agua Caliente on the edge of the Anza-Borrego Desert.

Martin Rodriguez in the hike-a-bike section before Alpine where mountain lion tracks were spotted. PC: Matteo Pistono

Dunham took the lead around mile 170 in the mountains. “I needed to sleep so I laid in the dirt and set my alarm for 20 minutes. I knew Marilyn was beating my door down, so I didn’t sleep soundly. I woke up after 10 minutes and just kept riding,” he said.

While a handful of riders did not bring a sleep system, most riders either used a bivouac or small bikepacking tent. PC: Matteo Pistono

Most of the mid-pack riders had bivyed the first night between mile 90 and 120 in the San Dieguito watershed, sleeping alongside the trail. Rising before sunrise, this spread-out group made their way along the Pacific Ocean in pairs and singles. Warm coastal breezes pushed the riders into the busy avenues of San Diego where many stopped in Little Italy for a slice of pizza or cappuccino. This was the last comfort before riding east out of the city into the mountains, where many spent the night in sleeping bags in 40-degree temperatures.

Riders taking a break a local eatery in Alpine. PC: Matteo Pistono

At the front of the race, Tait, Dunham and Rayner, still riding separately, made fast work of the 30 miles of white sand from Fish Creek Wash to Ocotillo Wells. Nearly the entire stretch was pummeling, sandy washboard that bruises sit bones so much to cause open sores. Every rider in this year’s race spoke of saddle sores after this section. At mile 294, the lead female racer Rayner pulled into the Iron Door Salon and wrote on social media “Fish Creek crushed my undercarriage, and I’m calling it at 300 miles at the Iron Door where they’re kindly letting me crash in a pew. Very, very bummed.”

Riders waking before dawn in Fish Creek Wash to cross the desert before the temperature spiked into the 100s. PC: Matteo Pistono

Tait chased Dunham on the tarmac to Borrego Springs. Both were unaware that Rayner had scratched. Tait caught Dunham just before Borrego Springs as both were attempting to arrive to buy burritos at Los Jilbertos, a famed Mexican restaurant, before the eatery closed for the night.

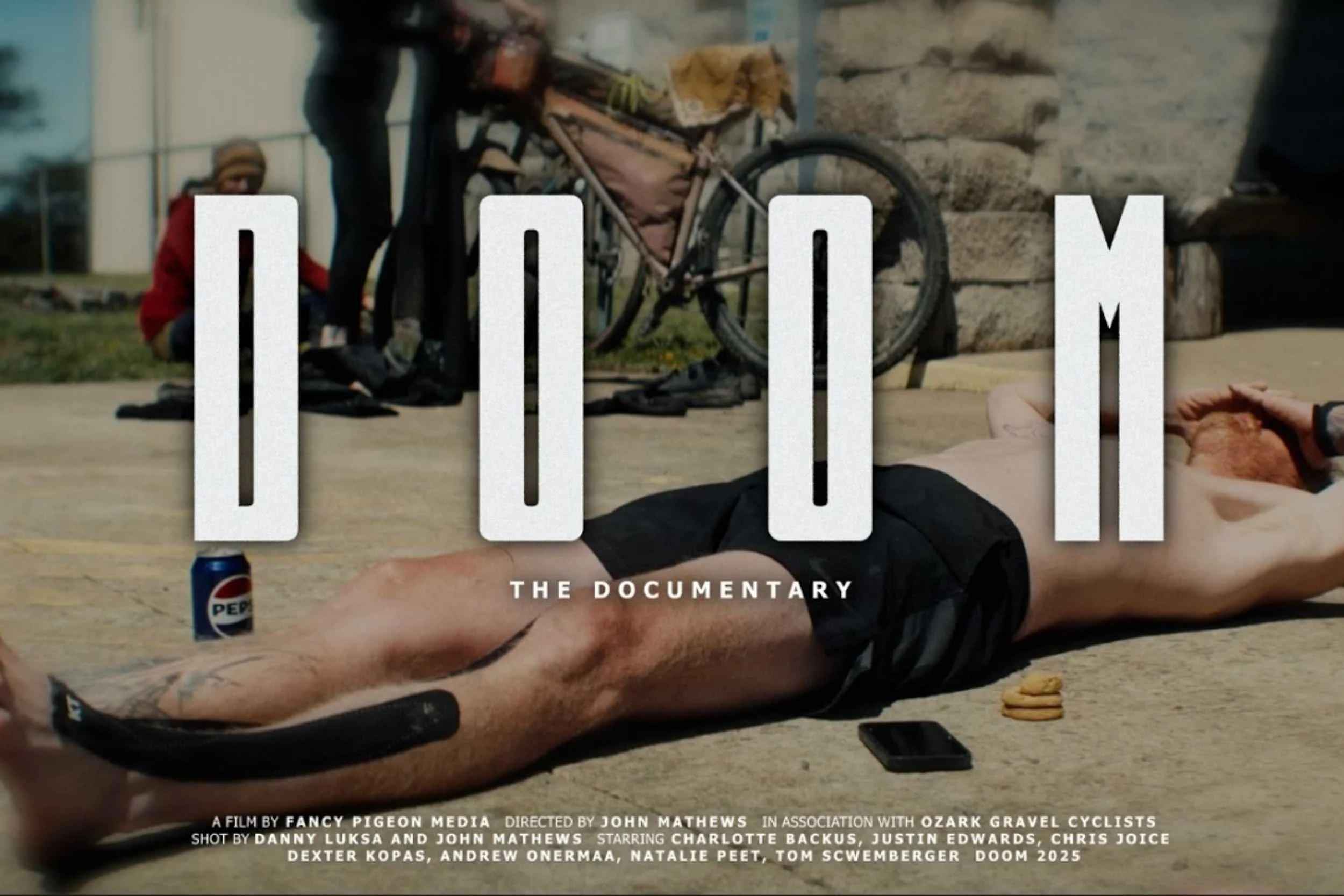

One of many sacrificial burritos during the Great Borrego Burrito Truce. PC: Tim Tait

Like prize fighters, the two had been trading blows for the entire race, chasing each other over the previous 300 miles. But it was over burritos they decided to ride the rest of the race together. “We made the Great Borrego Burrito Truce of 2021 in an effort to hit the sub-48-hour mark together,” Dunham said. “In the true bikepacking spirit, it was way more fun riding those last miles together.”

“It was great to have some camaraderie to work through that last tough sections at night,” Tait said.

Behind the leaders, riders continued to drop out of the race due to exhaustion and the effects of heat stroke from the first 150 miles. A total of 25 riders scratched. Seven-time finisher of the Stagecoach, Shelly Peppe-Nani said, “Sure, you can move quickly in the Stagecoach, but you must take care of yourself, manage hot spots, know when to throttle back. If not, you’ll flame out like many did this year.”

Ocotillo blooming in the desert outside of Borrego Springs. PC: Tim Tait

Chas Christiansen, chasing his 72-hour goal, said, “At Agua Caliente, I pulled in exhausted, filthy and beaten down. The coin operated hot shower and a burrito bought hours earlier and stashed in my bag brought me back to life.”

The market at Aqua Caliente is a critical watering source on the course. PC: Robert Jacobson

When riders in the midpack arrived at the edge of the white sand desert crossing, most chose to wait out the mid-day heat at Agua Caliente and ride across the desert at night. With headlamps illuminating the route, desert foxes, coyotes, and scorpions made glancing appearance to the riders. Leaving the washboard of Fish Creek Wash, then passing Borrego Spring on the highway, riders entered Coyote Canyon, which included negotiating the ankle to knee-deep flowing water of the Middle Willows. Stagecoachers pushed their bikes through this maze of willows, bamboo, and marshy thicket that ripped outwear and snagged the cables and bags on the bike. Exiting the willows, the sand and loose terrain returned.

Matteo Pistono negotiates the tangled maze of willow and bamboo in ankle to knee deep water of the Middle Willows. PC: Ian Kelly

The sand, washboard, and climbing in the last half of the route nearly broke many riders. “The lowest point for me was leaving Borrego Springs after forcing myself to eat a burrito for lunch—burrito the double-edged sword of bike packing!” Christiansen said. “I felt too full, sick to my stomach and thoroughly cracked, and it was only 11 am. The next 3 hours of climbing in deep sand during the heat of the day nearly broke me, overheated, overfilled, fighting for every mile through deep sand the finish never felt further away. You just need to keep going!”

Matteo Pistono’s hike-a-bike at the top of Coyote Canyon. PC: Ian Kelly

Most riders pushed their rigs through the sand and to the top of Coyote Canyon where they knew the finish line was near, though 3000 feet of tarmac, single track, and hike-a-bike remained. Tait said, “I couldn't sit on my seat after the desert washboards because my ass was so raw. That last 55 miles from Borrego Springs was very painful on the backside. I actually really enjoyed when we had a chance to hike our bikes [out Coyote Canyon].”

As Tait and Dunham climbed the last sections, Dunham had his low point in the race when he rolled over some pink plastic netting. He slammed on his brakes as the netting tangled around his gearing and legs. As he dismounted his bike, he realized there was no netting at all and that he was hallucinating. “I was tripping hard. Other than that, I actually felt great the entire time!”

Tait and Dunham finished together the 377 miles course with 28,000 feet of climbing, in a time of 49 hours 29 minutes. Tait slept 45 minutes and Dunham 10 minutes. They rode to the side of a local hotel and there, atop an old washing machine sat a notebook. They wrote their name and finishing time and then grabbed a hoppy IPA from the cooler at their feet.

Gregg Dunham holds the self-reported time in the notebook with Tim Tait in the background.

Brie Hevener was first female finisher with a time of 82 hours 51 minutes. “Not having done an event like this before, I’m really happy to have completed it and to have met so many amazing people on the way,” she said.

Carrie Hammond, Shelly Peppe-Nani, Tanya Pino, Brie Hevner (first woman to finish), and Angela Baker at Sunshine Market in Anza. PC: Tim Ingersoll

A total of 42 riders completed the course within the five-day cut-off.

Meg Knobel, the organizer of the Stagecoach 400, said after the race, “The highlights of the 10th anniversary Stagecoach 400 included the incredible trail conditions, a heightened sense of community and camaraderie after an extremely rough year for everyone dealing with COVID, and an impressive collection of strong finishing times all across the pack.”

There is no entry fee for the Stagecoach 400 and no prizes given. PC: Robert Jacobson

Riders are encouraged to donate to Outdoor Outreach, San Dieguito River Valley Conservancy, and San Diego Mountain Bike Association.

Matteo Pistono in the Indian Creek sector of Stagecoach 400. PC: Robert Jacobson